Agile is an implementation of Iterative Model. The spiral model is a software development process combining elements of both design and prototyping-in-stages, in an effort to combine advantages of top-down and bottom-up concepts.

The spiral model is a risk-driven process model generator for software projects. Based on the unique risk patterns of a given project, the spiral model guides a team to adopt elements of one or more process models, such as incremental, waterfall, orevolutionary prototyping.

This model was first described by Barry Boehm in his 1986 paper “A Spiral Model of Software Development and Enhancement”.[1] In 1988 Boehm published a similar paper[2] to a wider audience. These papers introduce a diagram that has been reproduced in many subsequent publications discussing the spiral model.

Spiral model (Boehm, 1988). A number of misconceptions stem from oversimplifications in this widely circulated diagram.[3]

These early papers use the term “process model” to refer to the spiral model as well as to incremental, waterfall, prototyping, and other approaches. However, the spiral model’s characteristic risk-driven blending of other process models’ features is already present:

[R]isk-driven subsetting of the spiral model steps allows the model to accommodate any appropriate mixture of a specification-oriented, prototype-oriented, simulation-oriented, automatic transformation-oriented, or other approach to software development.[2]

In later publications,[3] Boehm describes the spiral model as a “process model generator”, where choices based on a project’s risks generate an appropriate process model for the project. Thus, the incremental, waterfall, prototyping, and other process models are special cases of the spiral model that fit the risk patterns of certain projects.

Boehm also identifies a number of misconceptions arising from oversimplifications in the original spiral model diagram. The most dangerous of these misconceptions are:

- that the spiral is simply a sequence of waterfall increments;

- that all project activities follow a single spiral sequence; and

- that every activity in the diagram must be performed, and in the order shown.

While these misconceptions may fit the risk patterns of a few projects, they are not true for most projects.

To better distinguish them from “hazardous spiral look-alikes”, Boehm lists six characteristics common to all authentic applications of the spiral model.

The Six Invariants

Authentic applications of the spiral model are driven by cycles that always display six characteristics. Boehm illustrates each with an example of a “hazardous spiral look-alike” that violates the invariant.[3]

Define artifacts concurrently

Sequentially defining the key artifacts for a project often lowers the possibility of developing a system that meets stakeholder “win conditions” (objectives and constraints).

This invariant excludes “hazardous spiral look-alike” processes that use a sequence of incremental waterfall passes in settings where the underlying assumptions of the waterfall model do not apply. Boehm lists these assumptions as follows:

- The requirements are known in advance of implementation.

- The requirements have no unresolved, high-risk implications, such as risks due to cost, schedule, performance, safety, security, user interfaces, organizational impacts, etc.

- The nature of the requirements will not change very much during development or evolution.

- The requirements are compatible with all the key system stakeholders’ expectations, including users, customer, developers, maintainers, and investors.

- The right architecture for implementing the requirements is well understood.

- There is enough calendar time to proceed sequentially.

In situations where these assumptions do apply, it is a project risk not to specify the requirements and proceed sequentially. The waterfall model thus becomes a risk-driven special case of the spiral model.

Perform four basic activities in every cycle

This invariant identifies the four basic activities that must occur in each cycle of the spiral model:

- Consider the win conditions of all success-critical stakeholders.

- Identify and evaluate alternative approaches for satisfying the win conditions.

- Identify and resolve risks that stem from the selected approach(es).

- Obtain approval from all success-critical stakeholders, plus commitment to pursue the next cycle.

Project cycles that omit or shortchange any of these activities risk wasting effort by pursuing options that are unacceptable to key stakeholders, or are too risky.

Some “hazardous spiral look-alike” processes violate this invariant by excluding key stakeholders from certain sequential phases or cycles. For example, system maintainers and administrators might not be invited to participate in definition and development of the system. As a result, the system is at risk of failing to satisfy their win conditions.

Risk determines level of effort

For any project activity (e.g., requirements analysis, design, prototyping, testing), the project team must decide how much effort is enough. In authentic spiral process cycles, these decisions are made by minimizing overall risk.

For example, investing additional time testing a software product often reduces the risk due to the marketplace rejecting a shoddy product. However, additional testing time might increase the risk due to a competitor’s early market entry. From a spiral model perspective, testing should be performed until the total risk is minimized, and no further.

“Hazardous spiral look-alikes” that violate this invariant include evolutionary processes that ignore risk due to scalability issues, and incremental processes that invest heavily in a technical architecture that must be redesigned or replaced to accommodate future increments of the product.

Risk determines degree of detail

For any project artifact (e.g., requirements specification, design document, test plan), the project team must decide how much detail is enough. In authentic spiral process cycles, these decisions are made by minimizing overall risk.

Considering requirements specification as an example, the project should precisely specify those features where risk is reduced through precise specification (e.g., interfaces between hardware and software, interfaces between prime and sub contractors). Conversely, the project should not precisely specify those features where precise specification increases risk (e.g., graphical screen layouts, behavior of off-the-shelf components).

Use anchor point milestones

Boehm’s original description of the spiral model did not include any process milestones. In later refinements, he introduces three anchor point milestones that serve as progress indicators and points of commitment. These anchor point milestones can be characterized by key questions.

- Life Cycle Objectives. Is there a sufficient definition of a technical and management approach to satisfying everyone’s win conditions? If the stakeholders agree that the answer is “Yes”, then the project has cleared this LCO milestone. Otherwise, the project can be abandoned, or the stakeholders can commit to another cycle to try to get to “Yes.”

- Life Cycle Architecture. Is there a sufficient definition of the preferred approach to satisfying everyone’s win conditions, and are all significant risks eliminated or mitigated? If the stakeholders agree that the answer is “Yes”, then the project has cleared this LCA milestone. Otherwise, the project can be abandoned, or the stakeholders can commit to another cycle to try to get to “Yes.”

- Initial Operational Capability. Is there sufficient preparation of the software, site, users, operators, and maintainers to satisfy everyone’s win conditions by launching the system? If the stakeholders agree that the answer is “Yes”, then the project has cleared the IOC milestone and is launched. Otherwise, the project can be abandoned, or the stakeholders can commit to another cycle to try to get to “Yes.”

“Hazardous spiral look-alikes” that violate this invariant include evolutionary and incremental processes that commit significant resources to implementing a solution with a poorly defined architecture.

The three anchor point milestones fit easily into the Rational Unified Process (RUP), with LCO marking the boundary between RUP’s Inception and Elaboration phases, LCA marking the boundary between Elaboration and Construction phases, and IOC marking the boundary between Construction and Transition phases.

Focus on the system and its life cycle

This invariant highlights the importance of the overall system and the long-term concerns spanning its entire life cycle. It excludes “hazardous spiral look-alikes” that focus too much on initial development of software code. These processes can result from following published approaches to object-oriented or structured software analysis and design, while neglecting other aspects of the project’s process needs.

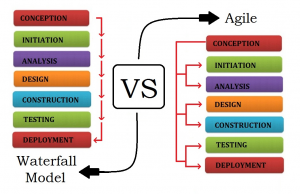

Agile and Spiral techniques; Differences/similarities.

The Spiral Model is iterative development. A typical iteration will be somewhere between 6 months and 2 years and will include all aspects of the lifecycle – requirements analysis, risk analysis, planning, design and architecture, and then a release of either a prototype (which is either evolved or thrown away, depending on the specific methods chosen by the project team) or working software. These steps are repeated until the project is either ended or finished.

Agile development, on the other hand, includes a number of different methodologies with specific guidance as to the steps to take to produce a software project, such as Extreme Programming, Scrum, and Crystal Clear. The commonality between all of the agile methods is that they are iterative and incremental. The iterations in the agile methods are typically shorter – 2 to 4 weeks in most cases, and each iteration ends with a working software product. However, unlike the spiral model, the software produced isn’t a prototype – it is always high quality code that is expanded into the final product.

Agile has more restrictions on it than spiral does. It’s a square/rectangle relationship – yes, agile is a spiral, but spiral isn’t agile and it’s separated by more than just “incremental execution in order of risk”. Agile accounts for shorter schedules and more frequent releases. Spiral tends to imply “big design up front” — where you plan out many spirals, each in order of risk. Spiral, however, isn’t Agile — it’s just incremental execution in order of risk.

Agile is spiral, but you create detailed plans for just one increment at a time. Agile adds a lot of other things, also. Spiral is a very technical approach. Agile, however, recognizes that technology is built by people. The Agile Manifesto has four principles that are above and beyond the Boehm’s simple risk management approach.

Agile is type of Iterative SDLC while spiral is type of Incremental SDLC. Scrum is one the type of Agile other are DSDM/FDD/XP etc. All SDLC after waterfall followed same set of acts(Requirement Analysis, Design, Coding and Testing) in some different combinations. So basic set of action in sequential OR Iterative OR Incremental are same.

- As far as Agile and Spiral are concern both have common advantage Changing Requirement handling.

- Short term releases.

- Risk management is easy due to shorter duration of SDLC.

- Cross team helps product and project going smooth.